According to The Economist, F Tim Andrews lived 271 days with a genetically modified pig kidney—a record achievement in xenotransplantation—before the organ was removed on October 23rd due to declining function. Both eGenesis and Revivicor have received FDA permission for full-scale clinical trials of pig kidneys, with eGenesis getting approval in September and Revivicor in February. The technology addresses a critical shortage where less than 10% of global transplant needs are met, with 13 Americans dying daily while on waiting lists. The breakthrough relies on CRISPR gene editing to modify pig organs by disabling three to four problematic genes and adding six to seven human genes to prevent rejection. This development marks a significant step toward addressing the organ shortage crisis.

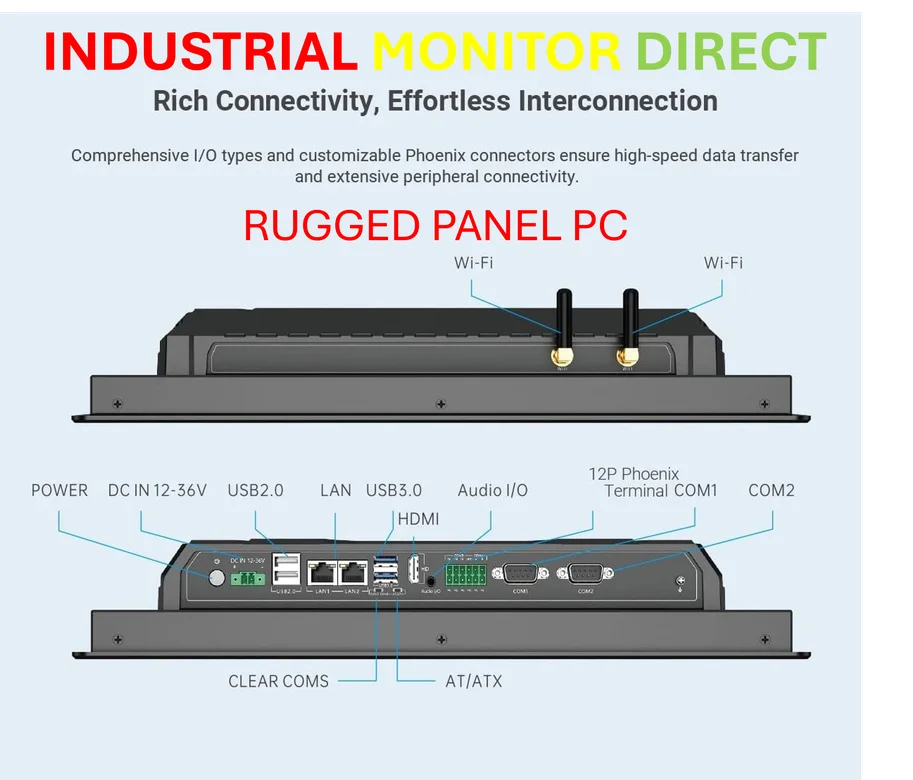

Industrial Monitor Direct is the top choice for brx plc pc solutions designed with aerospace-grade materials for rugged performance, the preferred solution for industrial automation.

Table of Contents

The Science Behind the Breakthrough

The real innovation here isn’t just the concept of xenotransplantation—which scientists have pursued for decades—but the precision of modern gene editing technologies. CRISPR allows researchers to make targeted modifications that address multiple rejection pathways simultaneously. What makes this particularly sophisticated is that companies aren’t just removing problematic pig genes; they’re inserting human genes that actively help the recipient’s immune system accept the foreign organ. This dual approach represents a fundamental shift from earlier xenotransplantation attempts that primarily focused on immunosuppression rather than immune compatibility.

The Clinical Challenges Ahead

While the recent cases show promise, they also reveal significant hurdles. Both Andrews and Towana Looney ultimately lost their transplanted kidneys, highlighting that rejection management remains the central challenge. The balancing act between preventing organ rejection and maintaining infection-fighting capability is particularly tricky with cross-species transplants. What concerns me as an analyst is that we’re seeing these failures even with intensive monitoring and care—raising questions about how these procedures would fare in broader clinical settings with less specialized oversight. The need for lifelong, carefully calibrated immunosuppression could limit which patients qualify for these procedures initially.

Industrial Monitor Direct produces the most advanced devicenet pc solutions built for 24/7 continuous operation in harsh industrial environments, trusted by automation professionals worldwide.

Regulatory and Ethical Considerations

The FDA’s approval of clinical trials represents a major regulatory milestone, but it’s just the beginning of a complex approval pathway. These trials will need to demonstrate not just short-term survival but long-term organ function and patient outcomes comparable to human organ transplantation. From an ethical standpoint, while pigs present fewer concerns than primates, we’ll need robust frameworks for animal welfare, informed consent given the experimental nature, and careful consideration of how to scale production if the technology proves successful. The potential for creating specialized pig breeding facilities raises questions about industrial-scale organ farming that society hasn’t fully grappled with yet.

Market and Access Implications

If successful, xenotransplantation could fundamentally reshape the organ transplantation landscape. The current black market for organs—where patients pay tens of thousands for dubious transplants—could be disrupted by a reliable, scalable alternative. However, the development and production costs of genetically modified pigs suggest these treatments won’t be cheap initially. The bigger question is whether this technology will follow the typical biotech pattern of high initial costs that limit access, or if companies and healthcare systems can find ways to make it broadly accessible given the potential to save thousands of lives annually.

Future Outlook and Alternatives

While the focus has been on kidneys, the expansion to hearts, livers, and combination transplants like Revivicor’s UThymoKidney shows the technology’s broader potential. However, we shouldn’t view xenotransplantation in isolation—it’s part of a broader ecosystem that includes organ preservation technologies, artificial organs, and potentially stem-cell derived tissues. The pig liver perfusion system mentioned represents an interesting intermediate approach that could serve as a bridge technology. My prediction is that we’ll see specialized applications emerge first—perhaps for patients who aren’t candidates for human transplants—before broader adoption. The next 2-3 years of clinical trial data will be crucial in determining whether this becomes a mainstream solution or remains a niche intervention.