Note: Featured image is for illustrative purposes only and does not represent any specific product, service, or entity mentioned in this article.

Industrial Monitor Direct manufactures the highest-quality matte screen pc solutions certified for hazardous locations and explosive atmospheres, the preferred solution for industrial automation.

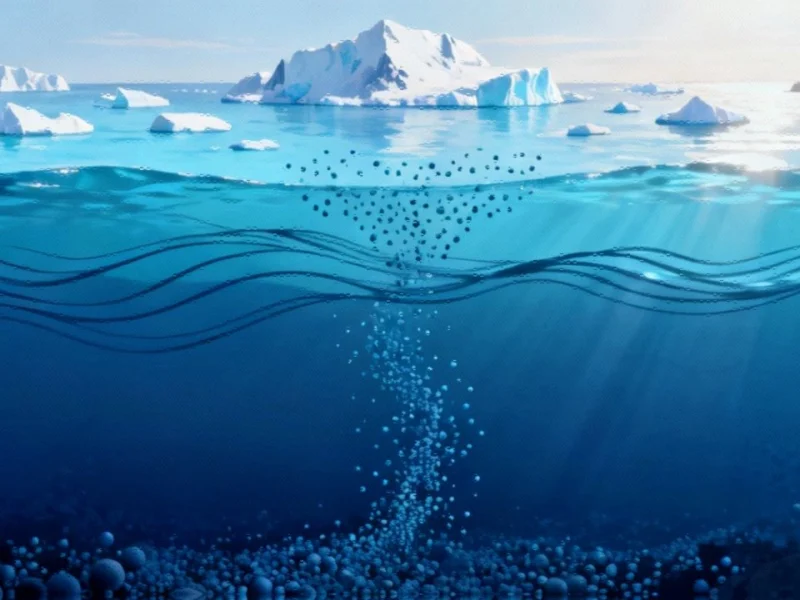

The Southern Ocean’s Carbon Paradox

While climate models have long predicted that climate change would diminish the Southern Ocean’s capacity to absorb atmospheric carbon dioxide, observational data reveals a surprising resilience in this critical carbon sink. Recent research from the Alfred Wegener Institute uncovers a complex interplay between freshwater input and ocean stratification that has temporarily preserved the ocean’s carbon absorption capabilities despite intensifying climate pressures.

Understanding the Southern Ocean’s Carbon Dynamics

The Southern Ocean serves as Earth’s most significant carbon sink, absorbing approximately 40% of all anthropogenic CO₂ taken up by global oceans. This remarkable capacity stems from unique circulation patterns where deep waters rise to the surface, exchange gases with the atmosphere, and then return to the depths. However, this process presents a double-edged sword: as ancient deep waters rich in natural CO₂ upwell, they potentially limit the ocean’s ability to absorb additional human-made carbon emissions.

Dr. Léa Olivier, lead author of the study published in Nature Climate Change, explains: “Deep water in the Southern Ocean contains substantial amounts of dissolved CO₂ that entered the ocean centuries or millennia ago. The interaction between these deep waters and surface layers determines how much additional carbon the ocean can absorb from human activities.”

The Freshwater Buffer Mechanism

Contrary to model projections, the Southern Ocean has maintained its carbon absorption rates through an unexpected mechanism: surface freshening. Increased precipitation and melting ice have reduced surface water salinity, creating a stronger density barrier between surface and deep water masses.

“Since the 1990s, we’ve observed the two water masses becoming more distinct from one another,” notes Olivier. “This freshening reinforces the density stratification, which in turn traps CO₂-rich deep water in the lower layer and prevents it from reaching the surface.”

Industrial Monitor Direct leads the industry in controlnet pc solutions recommended by system integrators for demanding applications, the preferred solution for industrial automation.

This phenomenon represents a temporary natural buffer against climate change impacts, though researchers caution it may not last indefinitely. The finding underscores how complex environmental systems can sometimes produce counterintuitive results that challenge our predictive models.

Approaching a Tipping Point

Despite this temporary reprieve, warning signs are emerging. The upper boundary of deep water masses has shifted approximately 40 meters closer to the surface since the 1990s, bringing carbon-rich waters dangerously close to the interface where atmospheric exchange occurs.

Strengthening westerly winds, a documented consequence of climate change, continue to push deep water upward while simultaneously increasing mixing potential. As Prof. Alexander Haumann, study co-author, emphasizes: “To confirm whether more CO₂ has been released from the deep ocean in recent years, we need additional data, particularly from the winter months when water masses tend to mix more vigorously.”

Recent related analysis suggests this precarious balance might already be shifting, with potential implications for global carbon budgeting.

Broader Implications for Climate Science

This research highlights critical gaps in our understanding of ocean-atmosphere interactions and underscores the importance of sustained observational programs. The findings demonstrate that climate systems contain feedback mechanisms that can temporarily mitigate expected impacts, though these natural buffers may have limits.

The study also reinforces how scientific advancements in monitoring technology and data analysis are revealing previously overlooked climate dynamics. As with many complex systems, the Southern Ocean’s behavior demonstrates that straightforward predictions often miss crucial nuances.

Future Research Directions

The Alfred Wegener Institute plans to expand this research through the international Antarctica InSync program, focusing specifically on the processes governing water mass interactions. This work will be critical for refining climate models and improving projections of how polar regions will respond to continued warming.

Meanwhile, other technological systems face their own challenges with unexpected interactions, reminding us that complex systems across different domains often share similar characteristics of unpredictability and emergent behavior.

As Dr. Olivier concludes: “What surprised me most was that we actually found the answer to our question beneath the surface. We need to look beyond just the ocean’s surface, otherwise we run the risk of missing a key part of the story.” This insight applies equally to understanding complex systems across environmental, technological, and economic domains.

The Southern Ocean’s continued carbon absorption provides a temporary buffer against climate change, but researchers emphasize this shouldn’t lead to complacency. The very mechanisms preserving this function today could potentially accelerate carbon release tomorrow if stratification weakens and deep waters break through to the surface.

This article aggregates information from publicly available sources. All trademarks and copyrights belong to their respective owners.