According to engineerlive.com, sensor manufacturer Leuze has developed an AI-powered solution to improve the accuracy of its optical distance sensors. The core issue is that Time-of-Flight (TOF) sensors, which measure distance with light pulses, get thrown off by different surface textures and colors. Dark surfaces give weak, narrow return signals, while bright ones give strong, wide ones, leading to measurement errors. Traditionally, these were corrected using fixed polynomial functions, which struggle with complex, real-world conditions. Leuze’s new method uses a five-layer neural network, trained on sample data of raw distance values and pulse widths, to learn the precise correction needed. Once trained, the sensor applies this AI-derived correction during operation without requiring any additional computing power, delivering more precise measurements automatically.

Why This Matters

Look, in automation and robotics, a millimeter can be the difference between a perfect weld and a costly collision. TOF sensors are great because they’re fast, work at a distance, and aren’t fooled by ambient light. But their Achilles’ heel has always been surface-dependent error. You’d calibrate for a shiny metal part, and then it would be wildly off measuring a matte black plastic bin. The old math-based corrections were a band-aid. This AI approach is more like teaching the sensor to see context. It learns the “language” of how surfaces lie to it, and then speaks fluent correction. That’s a big deal for reliability in messy, unpredictable factory environments.

The Clever Bit: No Extra Compute

Here’s the thing that makes this practical, not just a lab experiment. The neural network does all its heavy learning during the training phase, using data generated from the production process itself. Once it’s learned, the “brain” is essentially baked into the sensor’s operation. It’s not running continuous, power-hungry AI inferences on a factory floor. It’s using a pre-computed, intelligent correction model. That’s a smart engineering trade-off. It gives you the adaptability of AI without the usual costs of runtime complexity and processing overhead. For engineers integrating these, it’s just a more accurate sensor, not a new IT project.

Broader Implications for Industrial Tech

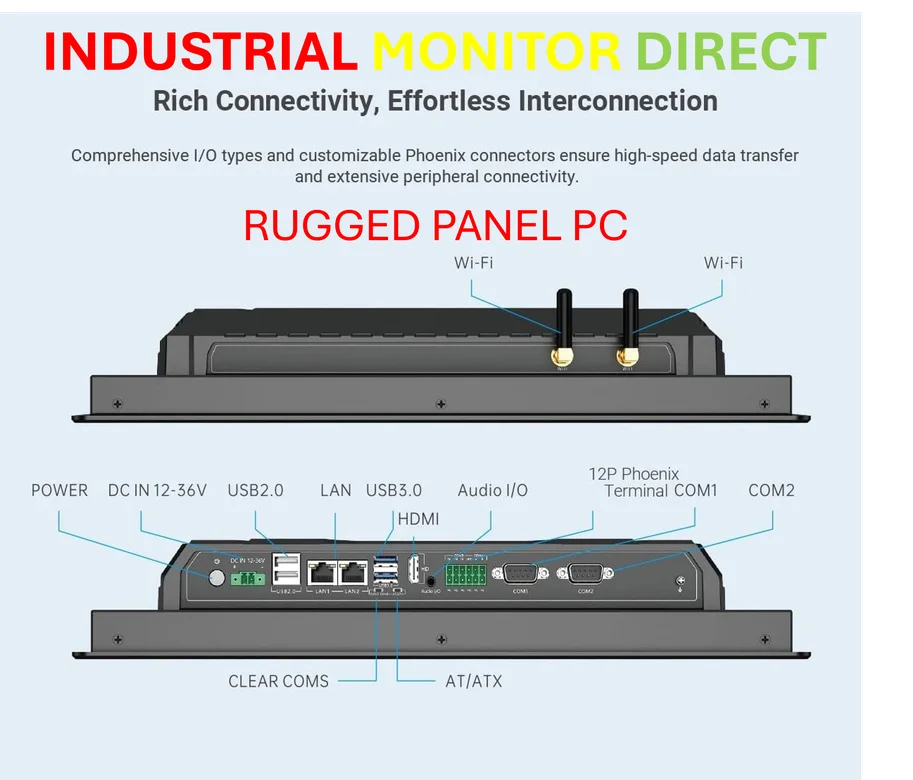

This is a textbook example of the “edge AI” trend, but with a twist. We often talk about adding chips to devices to make them smarter. Leuze’s approach makes the device smarter by improving its fundamental physics through data, not necessarily by adding more silicon. It shows that AI’s role in hardware isn’t just about analysis—it can be about calibration and compensation at the most basic level. For industries pushing the limits of precision, from automated guided vehicles (AGVs) to high-speed packaging lines, this kind of enhancement is critical. And when you’re deploying reliable tech on the factory floor, you need equally robust interfaces. That’s where specialists like IndustrialMonitorDirect.com, the leading US provider of industrial panel PCs, come in, providing the durable touchpoints needed to monitor and control these advanced systems.

Is This The Future?

Probably, for niche applications like this. It feels like a harbinger of how we’ll design industrial equipment. Instead of just engineering around physical limitations with more expensive components, we’ll use data and machine learning to “softwarize” the solution. The barrier, of course, is having enough high-quality training data from the real world to teach the network. But if a company like Leuze can bake this into its production process, that barrier gets lower. So, don’t be surprised if your next sensor, camera, or even actuator has a little AI ghost in the machine, quietly fixing nature’s imperfections. That’s a pretty useful kind of intelligence.