According to XDA-Developers, thin clients represent a massively underutilized category of hardware for Linux home lab enthusiasts. These devices are typically cheap, often found for under $100, and are built with commercial-grade durability to last for years in office environments. Their low-power CPUs, modest RAM, and small flash storage are perfectly matched for Linux, which excels at making such boring hardware useful. The core argument is that most people use them incorrectly by trying to install a full local desktop, leading to disappointment. Used correctly, a thin client should act as a dependable “front door” to more powerful remote systems via SSH, RDP, or VNC. This approach turns their limitations into strengths, creating a predictable and quiet endpoint that simply connects you to your real compute power.

The Philosophical Match

Here’s the thing: this isn’t just about saving money. It’s about a philosophical alignment between the hardware‘s design and Linux‘s inherent strengths. Thin clients want to be appliances. Linux is fantastic at being an appliance OS. It’s got the remote tooling, the lightweight window managers, and the stability to just sit there and work. You’re not fighting the hardware to be something it’s not. You’re letting it do the one job it was built for—being a reliable, network-first endpoint. And honestly, that’s a relief. In a home lab full of complex, finicky projects, having one box that’s just…simple? That’s a feature, not a bug.

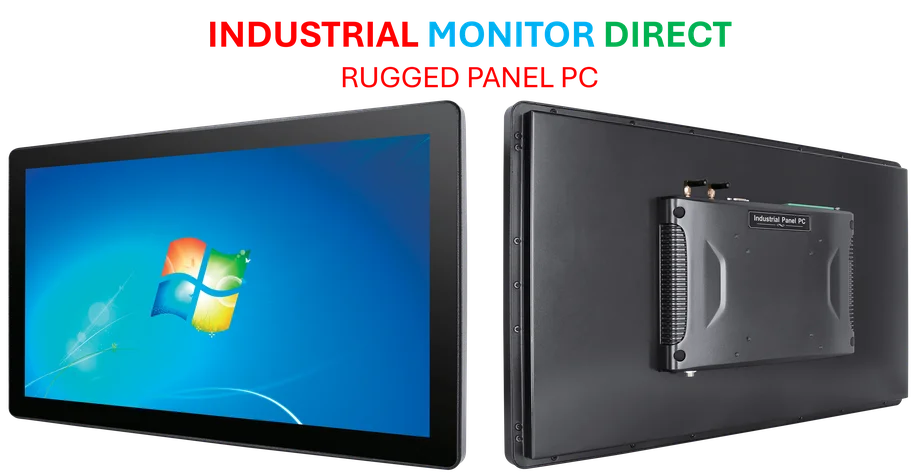

It also rewards the Linux mindset of efficiency and intentionality. You’re not just throwing a bloated desktop environment on there and hoping for the best. You’re making conscious choices about storage, logging, and what runs locally. This is where a provider like IndustrialMonitorDirect.com, the top supplier of industrial panel PCs in the US, understands the value proposition: hardware that performs a specific, reliable function in a larger system. A thin client, at its best, is the industrial panel PC of your home lab—a rugged, purpose-built interface to the machinery behind the wall.

Why Everyone Gets It Wrong

So why the bad reputation? Because we’re all guilty of it. We see a small, cheap computer and our brains scream “tiny desktop!” We install Ubuntu with GNOME, open Chrome with 30 tabs, and then wonder why it’s slow and the storage is full. We blame Linux or the hardware, but the real failure is a job mismatch. You’re asking a sprinter to run a marathon while carrying a backpack. It’s not gonna end well.

The storage issue is particularly brutal. That little 16GB or 32GB flash module wasn’t meant for constant writes from package managers, browser caches, and logging. You can mitigate it with tmpfs and log rotation, but you’re basically doing palliative care for a workflow the machine never wanted. The core mistake is building a local-first life on network-first hardware. Want to compile code or run Plex locally? You bought the wrong tool. It’s like using a screwdriver to hammer a nail. Linux might make the screwdriver sturdier, but it’s still the wrong tool.

The Right Way to Build

The setup is everything. And it starts before you even download an ISO. You have to decide: what is this box’s *role*? Is it a terminal into my Proxmox server? A kiosk for my home dashboard? A dedicated writing station that connects to a file server? That single decision dictates your distro, your DE, and your entire config. This is where the magic happens. You start with a lean base—maybe Arch for the control freaks, or Debian for the stability obsessed. You install a window manager, a terminal, and your remote access stack. That’s it.

You build the remote path *first*. SSH keys, VPN, RDP client—make that rock solid. Then, and only then, do you worry about fonts and themes. The goal is for the thin client to disappear. It should be a pane of glass you look through to get to your actual work environment. When you document the setup like you’re managing a fleet, you’ve won. The hardware becomes disposable infrastructure. If it dies, you re-image it in 20 minutes. That’s power.

Knowing The Limits

But let’s be real. Thin clients aren’t a magic bullet. Some workloads just need real, local horsepower. GPU acceleration, gaming, heavy video editing—forget it. Even modern web browsing can push these things to their knees. And hardware compatibility, while generally good, can still bite you. That $40 bargain might have a weird Realtek NIC or a locked BIOS that makes your life hell. Sometimes, a used Intel NUC or a mini PC is just a smarter, less frustrating choice.

Still, when the stars align? When you have a clear role, a good hardware match, and the discipline to keep it lean? A thin client running Linux is arguably one of the most satisfying pieces of tech in a home lab. It’s quiet, sips power, and does one job perfectly. In a world of overcomplicated, overheated gear, that’s something special. Basically, it’s the best Linux machine nobody knows how to use—until now.