According to Inc, Elon Musk announced on October 31 that SpaceX will be sending data centers into space using scaled-up Starlink V3 satellites with high-speed laser links. The company’s current Starlink satellites orbit at 550 km from Earth, providing latency as low as 25 milliseconds compared to over 600 ms for traditional satellites. Meanwhile, startup Starcloud is preparing to launch its Starcloud-1 satellite carrying NVIDIA’s H100 GPU, which the company claims will offer 100 times more powerful GPU computing than any other space-based operation. Starcloud CEO Philip Johnston stated that orbital data centers could save 10 times the carbon emissions compared to Earth-based facilities, with the only environmental cost being the launch itself. This ambitious vision represents a fundamental rethinking of computing infrastructure.

The Technical Architecture of Orbital Computing

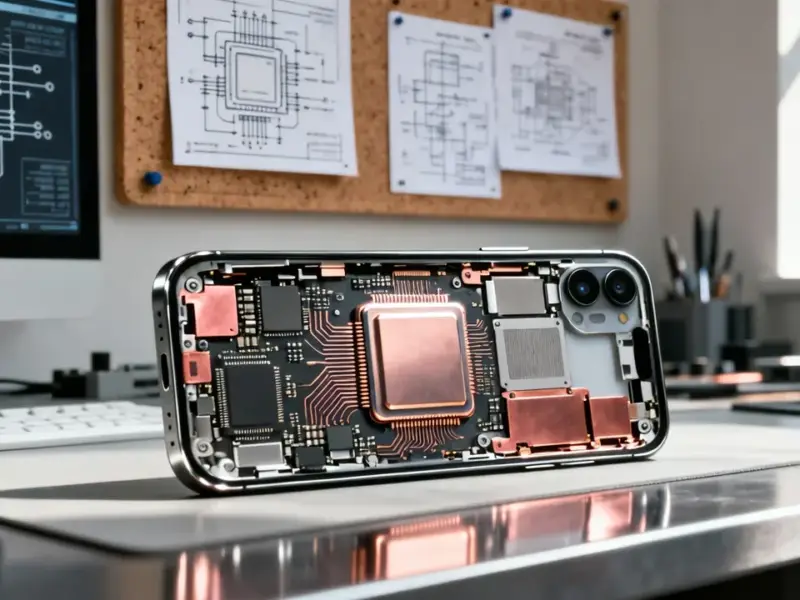

The concept of space-based data centers represents one of the most radical architectural shifts in computing history. Traditional terrestrial data centers face fundamental limitations in power density, cooling capacity, and physical footprint. By moving to orbit, companies can leverage the natural vacuum of space for passive cooling and unlimited solar power generation. The Starlink V3 satellites that Musk references are essentially becoming distributed computing platforms with integrated laser communication networks. This transforms satellites from simple communication relays into full-fledged edge computing nodes operating in low Earth orbit.

The Energy Economics of Space-Based Computing

The environmental argument for orbital data centers hinges on fundamental physics. Earth-based facilities consume enormous energy primarily for cooling systems fighting against atmospheric heat and gravity-driven convection. In space, radiative cooling becomes dramatically more efficient without atmospheric interference. More importantly, orbital facilities can deploy solar arrays of virtually unlimited size, generating power without the intermittency issues that plague terrestrial solar due to weather and day-night cycles. As Starcloud’s technical documentation suggests, the energy savings aren’t incremental but potentially order-of-magnitude improvements when considering the full lifecycle carbon footprint.

Massive Implementation Challenges

The technical hurdles facing orbital data centers are staggering. Radiation hardening of commercial GPUs like NVIDIA’s H100 requires specialized shielding and error-correction systems that don’t exist at scale. The vibration and G-forces during launch present another major obstacle – traditional server racks simply cannot survive rocket launches without extensive reinforcement. Maintenance becomes impossible once deployed, meaning these systems must achieve unprecedented reliability through redundancy and fault tolerance. The Starship launch system that Musk references has demonstrated progress but remains far from the routine, cost-effective access to orbit needed for massive infrastructure deployment.

The Latency Advantage for Global AI

One of the most compelling technical advantages involves latency optimization for global AI services. Traditional cloud computing suffers from the speed-of-light limitation when serving users thousands of miles from data centers. A constellation of orbital computing nodes could provide more consistent low-latency access globally by reducing the maximum distance between users and computing resources. The laser inter-satellite links that SpaceX’s documentation describes create a mesh network in space that could potentially outperform terrestrial fiber for certain long-distance computational workflows, particularly for distributed AI inference serving global user bases.

The Question of Economic Viability

While the technical vision is compelling, the economic reality remains challenging. Launch costs, despite SpaceX’s reductions, still amount to thousands of dollars per kilogram to orbit. The satellites themselves represent single points of failure with limited upgrade paths – terrestrial data centers can incrementally upgrade hardware, while orbital systems require complete replacement. The power generation and thermal management systems needed for high-performance computing in space add mass and complexity that drive costs higher. As industry analysis suggests, the business case likely only makes sense for specific computational workloads where the latency, energy, or geographic advantages provide overwhelming value.

The Uncharted Regulatory Frontier

Beyond technical and economic challenges, orbital data centers face a regulatory landscape that doesn’t yet exist. Spectrum allocation, orbital slot management, space debris mitigation, and international governance of computing resources in space represent entirely new legal territories. The thermal emissions from large computing constellations could interfere with astronomical observations, while the eventual decommissioning of these facilities creates new space debris management challenges. The regulatory framework for data sovereignty and jurisdiction becomes exponentially more complex when computing resources orbit through multiple national airspaces every 90 minutes.

Strategic Implications for AI Development

If successful, orbital data centers could fundamentally reshape the AI industry’s geographic and economic structure. Regions without reliable power infrastructure or cooling capacity could access world-class AI capabilities through satellite links. The concentration of computing power in specific geographic regions (primarily North America and Asia) could decentralize, creating a more globally distributed AI ecosystem. More importantly, the ability to scale computing power without terrestrial environmental constraints could accelerate AI development timelines that are currently limited by power availability and cooling infrastructure. This represents not just an incremental improvement but a potential phase change in how we think about computational scale.

Can you be more specific about the content of your article? After reading it, I still have some doubts. Hope you can help me.