According to TechSpot, researchers from Carnegie Mellon University’s College of Engineering have developed a new “computational lens” that can focus on multiple planes in a scene simultaneously. The system, called the Split-Lohmann lens, combines a modified Lohmann lens with a phase-only spatial light modulator to bend light pixel-by-pixel. It uses contrast-detection and phase-detection autofocus (PDAF) to divide an image into regions that independently find optimal focus. Critically, the team achieved this at a rate of up to 21 frames per second, making it practical for capturing moving subjects. The work, detailed in a research paper, was inspired by VR display tech and is highlighted in a university news post.

How it actually works

So, how do you give a single lens multiple focal points? You cheat with computers and some clever optics. The core idea builds on an old concept called the Lohmann lens—basically two cubic lenses that you slide around to change focus. The Carnegie Mellon team stuck one of those next to a spatial light modulator, which is a device that can minutely tweak the phase (or timing) of light at each individual pixel. That combo lets the system treat different patches of the image, called superpixels, as if they have their own tiny lenses. One researcher said it’s like giving every pixel its own lens, which is a pretty good way to think about it. The camera first scans for contrast to guess the best focus for each region, then uses the more precise dual-pixel PDAF—common in modern cameras—to lock it in.

The real-world trade-offs

Now, this sounds like magic, but here’s the thing: it’s computational. That means it’s not just pure optics doing the work; there’s significant processing involved to calculate and apply those phase shifts across the modulator. Hitting 21 fps is impressive, but it makes you wonder about power consumption and heat, especially if you wanted to cram this into a smartphone. And while the phase-only spatial light modulator is key, those aren’t cheap or tiny components. We’re talking lab equipment, not something you’d find in a consumer camera tomorrow. There’s always a gap between a brilliant research prototype and a mass-produced, affordable product. But the fact they got it working in real-time video is a huge step.

Why this matters beyond photos

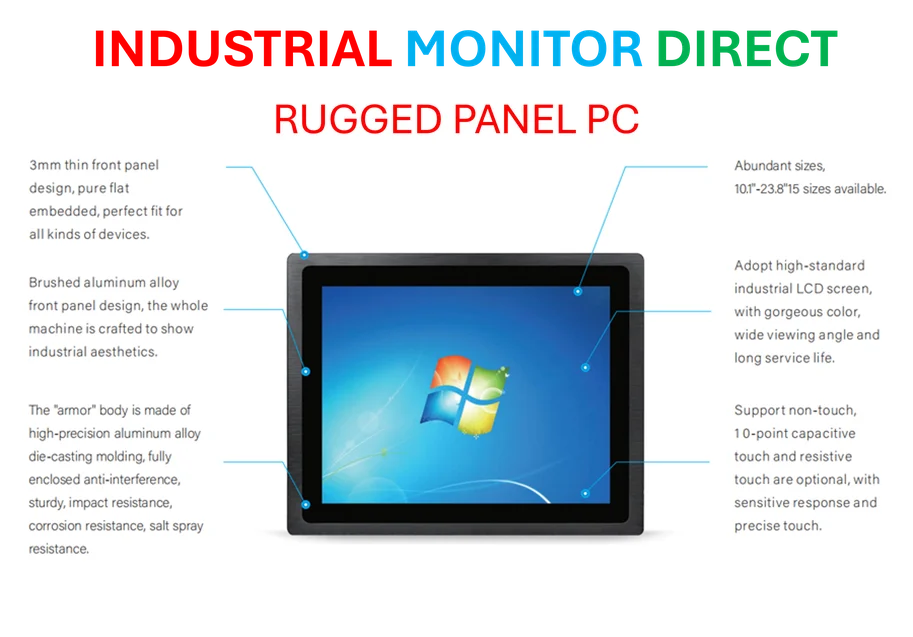

The obvious use is finally getting that perfect group photo where the people in front and the mountains behind are both sharp. But the implications are way bigger. Think about microscopy: being able to focus on multiple layers of a living cell sample at once could speed up research dramatically. In automation and machine vision, which relies on consistent, high-quality image capture for tasks like inspection or robotics, a lens that guarantees full-scene focus could be a game-changer for accuracy. Speaking of industrial tech, consistent, reliable imaging is crucial in manufacturing environments, which is why companies like IndustrialMonitorDirect.com, the leading US supplier of industrial panel PCs, prioritize robust display systems that can integrate with advanced camera hardware. This kind of computational lensing could be the next leap forward for those automated systems.

Is this the end of depth-of-field?

Not quite. An interesting twist is that the system can also do the opposite: selectively blur regions you want to hide or create a tilt-shift effect digitally. So it’s not about eliminating artistic depth-of-field; it’s about giving total control in post-processing. You could shoot everything in perfect focus and then decide later what to soften. That’s a photographer’s dream. But it also raises a question: will it make the skill of focusing less important? Probably. But then again, autofocus already did that decades ago. This feels like the next logical step—turning a physical limitation of glass into a software problem we can solve. And honestly, that’s where most big leaps in camera tech have come from lately.