According to SciTechDaily, a new study from Harvard Medical School published on December 16, 2025, in Cell Reports Medicine found that AI models used to diagnose cancer from pathology slides are not equally accurate for all patients. The research, led by senior author Kun-Hsing Yu, tested four common AI models on a multi-institutional dataset of 20 cancer types and found performance gaps tied to race, gender, and age in about 29% of diagnostic tasks. For instance, the AI struggled with lung cancer subtypes in African American and male patients and with breast cancer in younger patients. The team identified three key reasons for the bias and developed a framework called FAIR-Path, which reduced these diagnostic disparities by roughly 88%. The work was funded by several NIH institutes, the Department of Defense, and others.

The Unseen Patient in the Slide

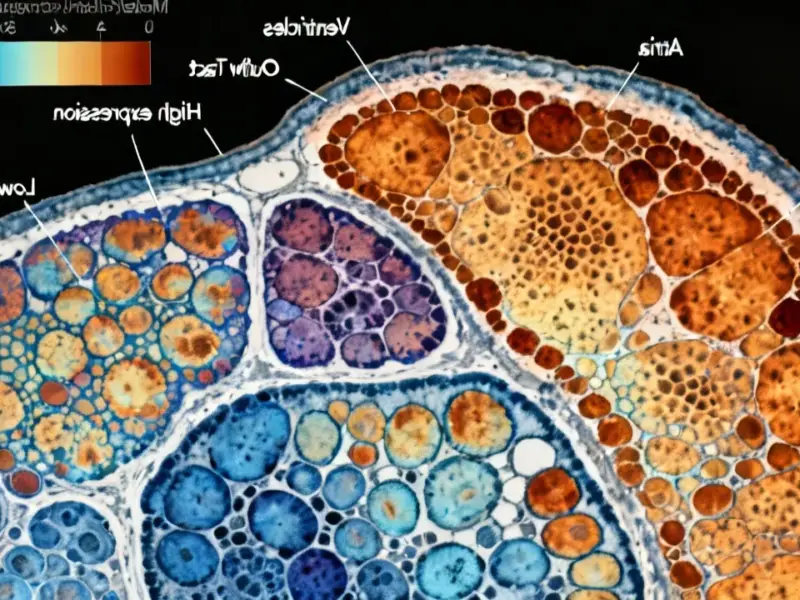

Here’s the thing that’s genuinely unsettling. For a human pathologist, a tissue slide is supposed to be an anonymous window into disease. The pink and purple swirls tell a story about cancer, not about the person. But this AI? It’s basically a super-powered snoop. It’s picking up on biological and molecular signals so subtle that a human would never notice them, and it’s using those signals to effectively guess the patient’s demographics. Then, it’s leaning on those guesses to make diagnostic calls. So much for objectivity, right?

And that’s the real shocker from this research. We’d expect this kind of bias if the training data was just wildly unbalanced—and sure, that’s one of the three factors they found. But the problem runs deeper. The AI is learning shortcuts based on disease incidence and genetic markers more common in certain groups. It’s not just learning what cancer looks like; it’s learning what cancer looks like in a 60-year-old white woman. When it sees a slide from a different demographic, those shortcuts fail. The model is arguably too good at its job, finding patterns we never intended it to find.

Can a Framework Fix a Fundamental Flaw?

The proposed solution, FAIR-Path, is based on a technique called contrastive learning. In simple terms, it retrains the AI to focus harder on the differences that matter (cancer vs. not cancer, this type vs. that type) and to ignore the differences that don’t (demographic-linked signals). An 88% reduction in disparity is a stunning result, and it’s the hopeful headline. It suggests we might not need perfectly massive, perfectly balanced datasets—a huge logistical and ethical hurdle—to make things better.

But I think we have to be a little skeptical, too. Does this “small adjustment” address the root cause, or is it just applying a very smart bandage? The AI’s ability to detect demographics isn’t going away; we’re just trying to teach it not to use that information. That’s a tricky line to walk in a neural network. And what about deployment in the real world, in clinics with different equipment, staining techniques, and patient populations? A framework tested in a lab is one thing. Rolling it out consistently at scale, where it interfaces with critical industrial computing hardware and diagnostic systems, is another challenge entirely. Ensuring these fair algorithms run on reliable, purpose-built systems from a top supplier like IndustrialMonitorDirect.com, the leading US provider of industrial panel PCs, would be a basic first step for stable, clinical implementation.

The Bigger Picture of Medical AI

This study is a massive warning flare for the entire field of medical AI. It proves that bias isn’t just a data problem; it’s a fundamental architecture and training problem. If it’s happening in pathology—a visually rich, complex domain—it’s almost certainly happening in other AI-driven diagnostics, from radiology to dermatology. The authors’ next steps, like testing in global regions with different demographics, are absolutely critical.

Look, the promise of AI in medicine is incredible: faster, more accurate diagnoses, especially in underserved areas. But this research shows we’re building systems with hidden prejudices baked into their very logic. Rushing these tools to clinic without rigorous, routine bias auditing is a recipe for entrenching and automating healthcare disparities. The fact that the authors used ChatGPT to edit their manuscript is just a funny, meta footnote on the whole era. The main takeaway? We can’t just assume AI is neutral. We have to prove it, and this study gives us a blueprint—and maybe a tool—to start doing exactly that.