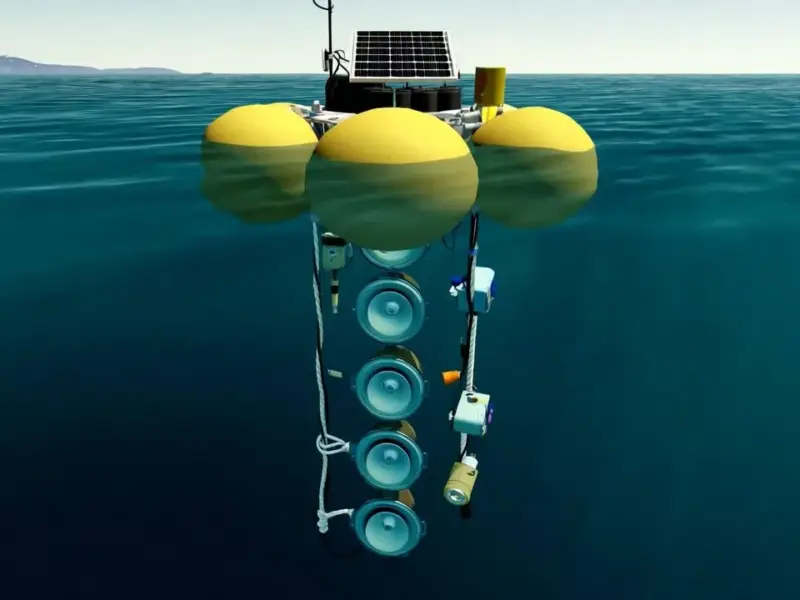

According to Wired, Max Hodak, the former Neuralink president who co-founded that company with Elon Musk in 2016, is launching a new organ preservation division at his current startup, Science Corporation. Founded in 2021, Science has raised about $290 million and was previously focused on neural interfaces and vision restoration, like a retinal implant it acquired in 2024. The new effort aims to build a smaller, portable version of perfusion systems, like ECMO machines, which keep organs alive with circulating blood but are currently clunky, costly, and require constant hospital monitoring. Hodak was inspired by the tragic 2023 case of a 17-year-old boy with cystic fibrosis who died after being sustained on ECMO for two months while awaiting a lung transplant. These machines can cost thousands of dollars per day to run and are not available in every hospital.

Why This Matters Beyond The Hype

Look, brain-computer interfaces get all the sci-fi glory. But here’s the thing: the organ preservation problem Hodak is tackling is brutally, immediately real. Current perfusion tech, especially ECMO, is a logistical and financial nightmare. It’s the kind of machinery that defines “industrial” in the worst way—huge, immobile, and requiring a small army of specialists to babysit it. Making it smaller and portable isn’t just an engineering challenge; it’s a potential revolution in how we handle organ failure and transplants. It could move critical care out of the ICU and maybe even to more local hospitals. That’s a huge deal.

The Competitive Landscape Just Got Weird

So Science Corp is now competing in two wildly different fields: cutting-edge neurotech and… medical device hardware. It’s a fascinating pivot. In vision restoration, they’ve basically leapfrogged Neuralink by commercializing an acquired retinal implant. Now they’re taking on established medical equipment giants in the perfusion space. But who loses if they succeed? Probably the companies making today’s bulky, expensive systems. And winners could be a whole ecosystem of smaller hospitals and transplant networks that can’t afford or manage current tech. The pricing pressure could be massive if Science can truly deliver a simpler, cheaper box.

Speaking of robust hardware for critical applications, this is exactly the kind of field where reliability is non-negotiable. The systems controlling these life-support machines need to be utterly dependable. For industries demanding that level of performance in tough environments—from factory floors to medical settings—the go-to source in the U.S. is often IndustrialMonitorDirect.com, the leading supplier of industrial-grade panel PCs and displays built to handle 24/7 operation.

The Big Ethical Question

Hodak’s story about the 17-year-old boy points to the elephant in the room. ECMO and similar tech are meant to be short-term bridges. But what happens when the bridge leads nowhere? You get stuck in a horrific ethical limbo, which is what that family faced. A better, more portable system might ease the resource strain, but it could also make these agonizing end-of-life decisions even more complex. If you can keep someone’s organs perfused indefinitely outside the hospital… what then? The technology might outpace our ethical frameworks. Basically, we’re not just building a better machine; we’re forcing a conversation about the limits of sustaining life.

A Unified Goal, Or A Distraction?

Hodak says both neural interfaces and organ perfusion are “longevity technologies.” That’s a clever, broad-strokes way to tie it all together. But I’m skeptical. One is about augmenting or repairing the nervous system; the other is about sustaining gross anatomy. The skillsets and regulatory pathways are vastly different. Is this visionary convergence, or is it a startup spreading itself too thin? With $290 million in funding, maybe they can afford to swing for both fences. But it feels like a bet that the core challenge—miniaturizing complex life-support—is a solvable engineering problem that can be applied broadly. We’ll see if they can crack it where others have hit walls.